A study of conscience crosses over between psychology and philosophy, because it raises questions about the origins and purpose of guilt feelings and feelings of shame in guiding human behaviour, and the relationship between three of the possible originators of moral behaviour: feelings, rules and a rational assessment, for example, of consequences. Consider, for example, the following questions:

Holman Hunt, The Awakening Conscience. Where guilt comes from, and its control over human behaviour, is a key issue.

All this presupposes that we are clear what conscience is. Is it a “voice” in our heads? Or a feeling in our belly? Is it a process of reasoning as Aquinas suggested, or something purely God-given, as Butler argued? Does our conscience come from an authority figure, as Fromm suggests, or from our upbringing, as Freud argued?

This has important implications for at least two issues. If our conscience is fallible (it can make mistakes) then it is still possible that there is an objective morality. If conscience is infallible, then it is impossible that there can be an objective morality because our consciences disagree so much with each other about issues of right and wrong that we are forced to concede the case for relativism. And if we think God is the originator of conscience, what do we say when God orders us, as apparently he did Joshua, to slay the people of Jericho and Ai (Joshua 6-8)?

There are also important implications, secondly, for the question of personal freedom and responsibility. If we are in thrall to an authority figure who becomes internalised, as Fromm argued, then are we really responsible for our actions?

Conscience is usually seen as an inner voice or sense of moral judgement. Here are some definitions:

“Conscience is our natural guide, assigned to us by the Author of Nature” (Joseph Butler)

“Conscience is the connecting spine and companion teacher of the soul whereby the soul is dissociated from evil and clings to good” (Origen)

‘Conscience is the reason making moral judgements’ (St Thomas Aquinas )

‘The built in monitor of moral action or choice values.’ (John Macquarrie)

There is no Hebrew word for conscience although a Greek word ‘synderesis’ (later picked up by Jerome and Aquinas) appears in the Book of Wisdom 17:11. St Paul mentions conscience as an awareness of what is good and bad. He values it as a measure of the pureness of our motives:

“ For this is what we boast about: our conscience testifies that we have conducted ourselves in the world with pure motives and godly sincerity, without earthly wisdom but with God’s grace-and especially towards you.” (2 Cor 1:12)

However, conscience can be weak or mistaken (1 Cor 8:10-12) and sometimes we may not have the will to act on it:

‘ I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate … I can will what is right, but I cannot do it. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want, is what I do.’ (Romans 7:15,18)

Paul believed conscience lay at the centre of our being, and it is something all human beings have irrespective of their faith.

‘ The Gentiles (ie non-Jews) can demonstrate the effects of the law engraved on their hearts, to which their own conscience bears witness .’ (Romans 2:15)

To act in accordance with conscience is to act with integrity based on inner conviction. It is to be true to ourselves. But as Romans 7 illustrates, this often involves struggle and conflict within, with feelings of powerlessness, guilt and inadequacy.

Aquinas distinguished between an innate source of good and evil, synderesis (literally, one who watches over us) and a judgement derived from our reason, conscientia.

Thomas Aquinas sought to reconcile the Bible’s view of conscience as God-given with human free will.

In synderesis, Thomas Aquinas saw conscience as an innate instinct for distinguishing right from wrong. Synderesis can be defined as “a natural disposition of the human mind by which we instinctively understand the first principles of morality”. Aquinas (optimistically) thought people tended towards goodness and away from evil (the ‘synderesis rule’). This principle is the starting point of Aquinas’ natural law system of ethics.

Aquinas identified conscience (conscientia) as the power of reason for working out what was good and what was evil, the “application of knowledge to activity”. This is something closer to moral judgement rather than instinct. In practice conscientia is something similar to Aristotle’s phronesis or practical wisdom. We cannot flourish without it. In practical situations we have to make choices and to weigh alternatives, and we do so by using our conscience.

However, conscience can make mistakes and needs to be trained in wisdom. At times people do bad things because they make a mistake in discriminating good from evil. Aquinas believed that if the conscience has made a factual mistake, for example, if I don’t realise that my action breaks a particular rule, then my mistaken conscience is not to blame. But if I am simply ignorant of the rule (such as not committing adultery), I am to blame.

Taking a rather bizarre example, Aquinas argues that if a man sleeps with another man’s wife thinking she was his wife, then he is not morally blameworthy because he acted “in good faith”.

“Conscience is reason making right decisions and not a voice giving us commands” (Summa Theologica, I-II, Q19 A 5 &6).

Conscience deliberates between good and bad. Aquinas notes two dimensions of moral decision making, “Man’s reasoning is a kind of movement which begins with the understanding of certain things that are naturally known as immutable principles without investigation. It ends in the intellectual activity by which we make judgements on the basis of those principles…” (Summa Theologica, 1-1, Q79)

So Synderesis is right instinct or disposition, the awareness of the moral principle to do good and avoid evil. Conscientia is right reason, which distinguishes between right and wrong as we make practical moral decisions.

Exercise: distinguish between synderesis and conscientia in Aquinas’ view of conscience. If necessary use the Extract from Summa Theologica on this website.

Joseph Butler was an Anglican theologian who identified conscience as the ultimate moral decision-maker.

Butler’s view of conscience as innate, something we are born with and given by God to guide us, is subtly different from Newman’s.

‘ There is a principle of reflection in men by which they distinguish between approval and disapproval of their own actions … this principle in man … is conscience’ (Butler, Fifteen Sermons, 1726: 21).

Butler argued that humans were influenced by two basic principles, self-love and love of others. In Butler’s view, conscience directs us towards acting for the happiness or interests of others instead of focusing on ourselves.

Like Aquinas, Butler argued that conscience determines and judges the rightness and wrongness of actions. He went on to say that conscience operates in situations without any introspection and is the ultimate authority in ethical judgements.

‘ Had it strength as it has right; had it power as it had manifest authority, it would absolutely govern the world.’ (Butler, Fifteen Sermons, 1726).

Conscience gives instant intuitive judgements about what we should or should not do. It is, ‘our natural guide, the guide assigned us by the Author of our nature’. Conscience is a guide to moral behaviour, innate, placed within us by God, Butler calls it “the law of our nature” and, given its divine origin, must be obeyed: ‘it is our duty to walk in that path, and follow this guide without looking about to see whether we may not possibly forsake them with impunity.’ If your conscience instructs you to act in a certain way you have complete authority to do so without considering alternatives. You obey the commands of your consciences without reservation. This is a far more intuitive view of conscience than Aquinas’ account, and raises the serious moral question: what happens if our conscience is telling us to do something most people would accept as morally wrong?

“But allowing that mankind hath the rule of right within himself, yet it may be asked, ‘What obligations are we under to attend to and follow it?’ I answer: it has been proved that man by his nature is a law to himself, without the particular distinct consideration of the positive sanctions of that law; the rewards and punishments which we feel, and those which from the light of reason we have ground to believe, are annexed to it. The question then carries its own answer along with it. Your obligation to obey this law, is its being the law of your nature. That your conscience approves of and attests to such a course of action, is itself alone an obligation. Conscience does not only offer itself to show us the way we should walk in, but it likewise carries its own authority with it, that it is our natural guide, the guide assigned us by the Author of our nature; it therefore belongs to our condition of being, it is our duty to walk in our path, and follow this guide without looking about to see whether we may not possibly forsake them with impunity .” (Butler, Fifteen Sermons, 1726: 6).

Exercise: outline Butler’s view of conscience, using the above extract.

I n Butler’s view, conscience makes intuitive moral judgements and has absolute authority. This view may be challenged as it is conceivable that conscience coul d be misled or misinformed. If conscience has absolute authority and should be obeyed unquestioningly, it could be used to justify any action.

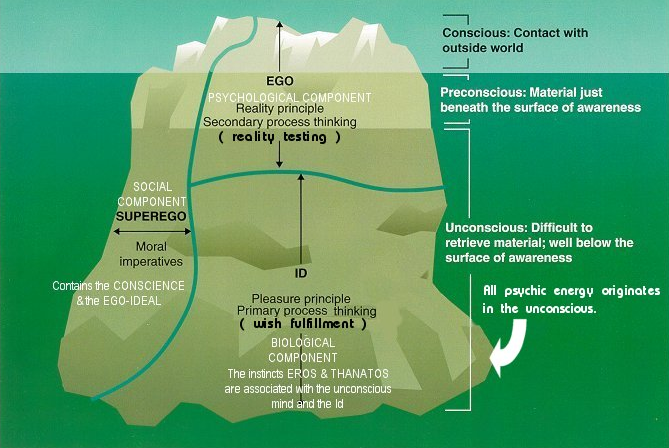

An alternative approach to conscience comes from Sigmund Freud. In his book, “The Outline of Psychoanalysis”, (1949) he wrote that the human psyche is inspired by powerful instinctive desires that demand satisfaction.

These desires surface at our birth and are critical to our behaviour up to the age of 3 years. In this period Freud argues infants are driven entirely by the ‘pleasure principle’. These overriding desires and their pleasurable satisfaction (for food, comfort, for example) drive the id . The id develops two broad categories of desire, according to Freud. Eros is the life-instinct, which gives us the desires for food, self-preservation, and sex. Thanatos is the death-instinct, which drives desires for domination, aggression, violence and self-destruction. These two instincts are at war within the id, and need to be tempered by ego constraints and by conscience.

Children learn that authorities in the world restrict the extent to which these desires are satisfied. Consequently, humans create the ego which takes account of the realities of the world and society. The ego Freud referred to as the reality principle, because our awareness of self and of others is crucial to our interaction with the world around us, and is formed at the age of 3 to 5 years. So the reality principle – the pragmatic idea that I should judge whether a course of action will result in overall pleasure or pain and so is in a sense serving my ego-identity, can easily get into conflict with the drives of the id. I learn as a child, for example, that always grabbing things from my playmates causes my playmates to disappear quite quickly. There is more to long term pleasure than instant gratification (synoptic point – is there a hint of Mill’s higher and lower pleasures here?).

Thirdly, Freud argued that a superego develops from 5 years onwards, which internalises and reflects disapproval of others. So when our parents praise or blame us, frown and smile, we absorb a sense of shame at disapproval, and pleasure at approval. In this way the superego forbids certain actions and produces a sense of guilt. The superego is the seat of values and ideals – except we need to remember they are produced by our upbringing, not our reason. The superego can easily assume the voice of the scolding, critical parent, keeping us ‘infantile’ and severely restricting our ability to grow a mature sense of self. Just as parents may be in conflict with a child, punishing and blaming, so the superego can be in conflict both with the id (passions0 and the ego (the sense of self in the world). The Freudian model of the psyche is illustrated below.

The superego grows into a life and power of its own irrespective of the rational thought and reflection of the individual: it is programmed into us by the reactions of other people. While we might think that Freud would want us to live by reason, in fact this ‘superego’ conscience restricts humans’ aggressive powerful desires (Greek, thanatos or death instinct within the id) which would otherwise destroy us. So guilt “expresses itself in the need for punishment” (Civilisation and its Discontents 1930:315-6). Eric Fromm, quoting Nietszche, agrees with Freud’s analysis of the destructive nature of the authoritarian conscience.

“Freud has convincingly demonstrated the correctness of Nietzsche’s thesis that the blockage of freedom turns man’s instincts “backward against man himself. Enmity, cruelty, the delight in persecution…- the turning of all these instincts against their own possessors: this is the origin of the bad conscience” (Eric Fromm, Man For Himself, 1947:113)

However, it is also possible for us to repress the sense of shame and guilt. Our superego can lead us to internalise shame, and to experience conflicts between the id desires and the shame emanating from the superego responses. The more we suppress our true feelings, the more that which drives us comes from what Freud described as the subconscious, which like an iceberg lies hidden in the recesses of our minds.

This repression of shame can cause pathological behaviour such as obsessive washing rituals experienced by Lady Macbeth as she mumbles “out, out damned spot! Will not all the waters of Arabia cleanse this little hand?”, a guilty reaction to Duncan’s murder. Although Lady Macbeth’s guilt was real, as she persuaded Macbeth to murder Duncan by “screwing his courage to the sticking place” as he wavered in resolve, yet the repetitive washing ritual illustrates how guilt can drive you mad. And sometimes, depending on our upbringing, the guilt is irrational , to do with our sexuality, for example, over which we may have no control. For further reading on Freud’s model of the conscious and subconscious worlds, click here.

Case Study: the footballer Paul Gascoigne suffers from an obsession to tidy and order things, even in the houses of friends he visits. In his autobiography he recounts this story of what happened to him as a young child, which may explain this pathological behaviour.

Paul Gascoigne has struggled with mental health problems despite being the star of the 1996 world cup team.

One day, when I was ten, I took Keith’s little brother Steven with us, telling his mam I would look after him. I was mucking about in the shop when Steven ran out into Derwentwater road in front of a parked ice-cream van. He didn’t see an oncoming car and it went right into him.

I ran out and stood in front of the crumpled little body, screaming, “Please move! Please move!”. His lips seemed to move slightly, but soon he was completely still. …I just had to sit there, watching him die. (Gazza- My Story page 28)

Exercise: How would a Freudian psychologist explain Paul Gascoigne’s obsession with tidiness?

Later psychologists modified Freud’s theory. They argued that conscience has a mature and immature dimension. The mature aspect is healthy and is identified with the ego’s search for integrity. It is concerned with right and wrong, and acts dynamically and responsively on things of value. The mature conscience looks outwards to the world and the future, developing new insights into situations. The immature conscience comprises the mass of guilty feelings which humans acquire in their early years from parental and school discipline. These feelings have little to do with the rational importance of the action. The immature conscience acts out a desire to seek approval from others instead of the principles and beliefs of the person.

Piaget an educational psychologist who conducted an experiment to try to discover how conscience develops. He found that up to the age of ten, children judge rightness or wrongness according to the consequences of an action (eg I pile baked bean tins behind a door, as they crash down they make a terrible noise. The younger child feels guilty). Older children begin to link rightness and wrongness with motive and intention. In the above example, the child did not want or intend to scatter the baked bean cans, so the older child reasons “I’m not guilty”!

These psychological account of conscience undermines both Aquinas’ and Butler’s religious theories of conscience because a. it is environmentally induced by upbringing, not innate and b. it is highly deterministic, because humans are driven, according to Freud, by forces operating out ofour subconscious minds. It doesn’t rule out the possibility that God has some involvement with conscience (in originating a moral faculty, for example), but if environment operates so strongly on conscience the religious theories need reworking.

Cardinal John Henry Newman took a more intuitionist approach than Aquinas. He wrote that

“Conscience is a law of the mind … a messenger of him, who, both in nature and in grace, speaks to us behind a veil, and teaches and rules us by his representatives. Conscience is the aboriginal (ie original or natural) vicar of Christ.” (John Henry Cardinal Newman, Letter to the Duke of Norfolk).

Newman believed that following conscience was following divine law. Conscience is a messenger from God, and it is God speaking to us. Newman was a devout Catholic, but said in a letter ‘I toast the Pope, but I toast conscience first’. Catholics are obliged to do what they sincerely believe to be right even if they are mistaken. In a commentary to the Vatican documents, a brilliant young theologian named Joseph Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict) seems to agree.

“ Over the Pope as the expression of the binding claim of ecclesiastical authority there still stands one’s own conscience, which must be obeyed before all else, if necessary even against the requirement of ecclesiastical authority.” (Pope Benedict in “Herbert Vorgrimler’s Commentary on the documents of Vatican II,” London, 1968:139)

This has led to tensions over ethical debates where individual conscience comes up against moral absolutes, such as the absolute condemnation of abortion and contraception. The Church teaches that using artificial contraception is intrinsically wrong because it breaks the intrinsic link between sex and reproduction.Yet many couples ignore this teaching and maintain the inherent goodness of birth control to limit population growth, or maintain choices over careers.

So the Roman Catholic Church’s teaching on conscience reflects both Newman and Aquinas and it holds that conscience is the law that speaks to the heart: ‘conscience is a law written by God’ (“Pastoral Constitution, Gaudium et Spes”).

Exercise: Explain the similarities or differences between Newman’s view of conscience and the view of Pope Benedict XVI.

Eric Fromm experienced all the evil of Nazism and wrote his books to reflect on how conscience and freedom can be subverted even in the most civilised societies. In order to explain how, for example, Adolf Eichmann can plead at his trial for mass murder in 1961 that he was only “following orders” in applying the final solution, we can invoke Fromm’s idea of the authoritarian conscience.

Eric Fromm was a child of the Holocaust and sought to explain how a civilised people could descend into barbarity.

The authoritarian conscience is the internalised voice of the external authority, something close to Freud’s concept of the superego considered above.

This internal voice may be backed up by fear of punishment, or spurred on by admiration or can even be created because I idolise an authority figure, as Unity Mitford did Adolf Hitler. As Unity found, this blinds us to the faults of the idolised figure, and causes us to become subject to that person’s will, so that “the laws and sanctions of the externalised authority become part of oneself” (1947:108).

Notice that the voice of the authoritarian conscience is obeyed not because it is good but because it is in authority. So, as with the Nazis, ordinary seemingly civilised human beings do atrocious evil because they are subject to a voice which comes essentially from outside them, bypassing their own moral sense. The presence of the authority figure is necessary to strengthen and maintain this voice, otherwise it loses its power and Fromm’s second concept of conscience, the humanistic conscience considered below, can reassert itself.

This authoritarian conscience can come from:

• Projection onto someone of an image of perfection.

• The experience of parental rules or expectations.

• An adopted belief system, such as a religion, with its own authority structure.

“Good conscience is consciousness of pleasing authority, guilty conscience is consciousness of displeasing it” (Eric Fromm 1947:109)

The individual’s identity and sense of security thus become wrapped up in the authority figure, and the voice inside is really someone else’s voice. This also emans obedience becomes the cardinal virtue, and as Eichmann pleaded at his trial, the individual feels he or she ahs no choice but to obey. The individual gives up the right to criticise, to reflect and to evaluate what the authoritarian conscience dictates.

“Those subject to him are means to his end and, consequently his property, and used by him for his purposes” (Fromm 1947:112)

So in choosing to obey the authoritarian conscience the individual loses their autonomy and creativity, or any action which does not obey the rules of the authority, is seen as rebellion and as in the archetypal story of Cain and Abel, when Cain kills his brother he is cast out forever, and complains “my punishment is more than I can bear”.

Fromm stresses that there are two implications: one where someone submits to authority and another where “he takes on the role of authority by treating himself with the same cruelty and strictness” and “destructive energies are discharged by taking on the role of the authority and dominating oneself as servant” (1947:113). Because of the authoritarian conscience we treat ourselves extra harshly, and become our own source of guilt and self-punishment.

“Paradoxically, authoritarian guilty conscience is a result of feelings of strength, independence, productiveness and pride, while the authoritarian good conscience springs from feelings of obedience, dependence, powerlessness and sinfulness.” (Fromm 1947:112).

Exercise: Read the story of Cain and Abel in Genesis. Fromm describes this as an archetype of the effects of an authoritarian conscience. Explain in your own words how Cain’s experience may be a reflection of the consequences of an authoritarian conscience.

Exercise: Thomas More’s conscience takes on the absolute authority of Henry VIII, in this YouTube clip of Robert Bolt’s ‘Man for All Seasons’. watch the clip and explain how More is rejecting the authoritarian conscience.

The humanistic conscience, in contrast, is “our own voice, present in every human being, and independent of external sanctions and rewards” (1947:118). Fromm sees this voice as our true selves, found by listening to ourselves and heeding our deepest needs, desires and goals.

The result of so listening is to release human potential and creativity, and to become what we potentially are; “the goal is productiveness, and therefore, happiness” (1947:120). This is something gained over a life of learning, reflection and setting and realising goals for ourselves.

Fromm sees Kafka’s The Trial as a parable of how the two consciences in practice live together. A man is arrested, he knows not on what charge or pretext. He seems powerless to prevent a terrible fate – his own death – at the hands of this alien authority. But just before he dies he gains a glimpse of another person (Fromm’s other conscience) looking at him from an upstairs room.

“His glance fell on the top storey of the house adjoining the quarry. With a flicker as of a light going up, the casements of the window suddenly flew open: a human figure, faint and insubstantial at that distnce and that height, leaned abruptly far forward and stretched both arms still farther. Who was it? A friend? A good man? Someone who sympathised? Someone who wanted to help? Was it one person only? Or were they all there? Was help at hand? Were there some arguments in his favour that had been overlooked? Of course. there must be. Logic is doubtles unshakeable, but it cannot withstand a man who wants to go on living. Where was the judge whom he has never seen? Where was the court, to which he had never penetrated? He raised his hands and spread out all his fingers”. Franz Kafka, The Trial

Exercise: to what extent can Kafka’s The Trial be seen as the story of the two consciences described by Eric Fromm.

Evaluation exercise; try marking this essay from Kesteven and Grantham Girls’ School, “Discuss Critically the View that Conscience is the Voice of God”.

St. Augustine of Hippo (334-430): De Trinitate

St. Thomas Aquinas (1224-1274): Summa Theologica, 1273

Joseph Butler (1692-1752): Fifteen Sermons, 1726

Eric Fromm (1900-1980) Man For Himself, 1947

John Henry Newman (1801-1890) The Grammar of Assent

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939): The Outline of Psychoanalysis, 1938; Civilisation and its Discontents, 1930

Glossary

Conscientious objection – the refusal to comply, usually with fighting a war, on account of conscience.

Ego – The inner dimension of human nature which takes account of the realities of the world and society according to Freud. Freud talks about the ‘reality principle’.

Super ego – The inner policeman which replaces the role of parents perceived in a pre rational human according to Freud. Freud talks about projections of the ‘ideal’/

Id – the early stage of human development concentrates on the satisfaction of the source of desires and needs, the Id. Freud talks about the ‘pleasure principle’.

Synderesis principle – Aquinas’ belief that people innately tend towards goodness and away from evil. We are born with an intuitive sense of first principles – the primary precepts – which orientate us by our very natures towards the good.